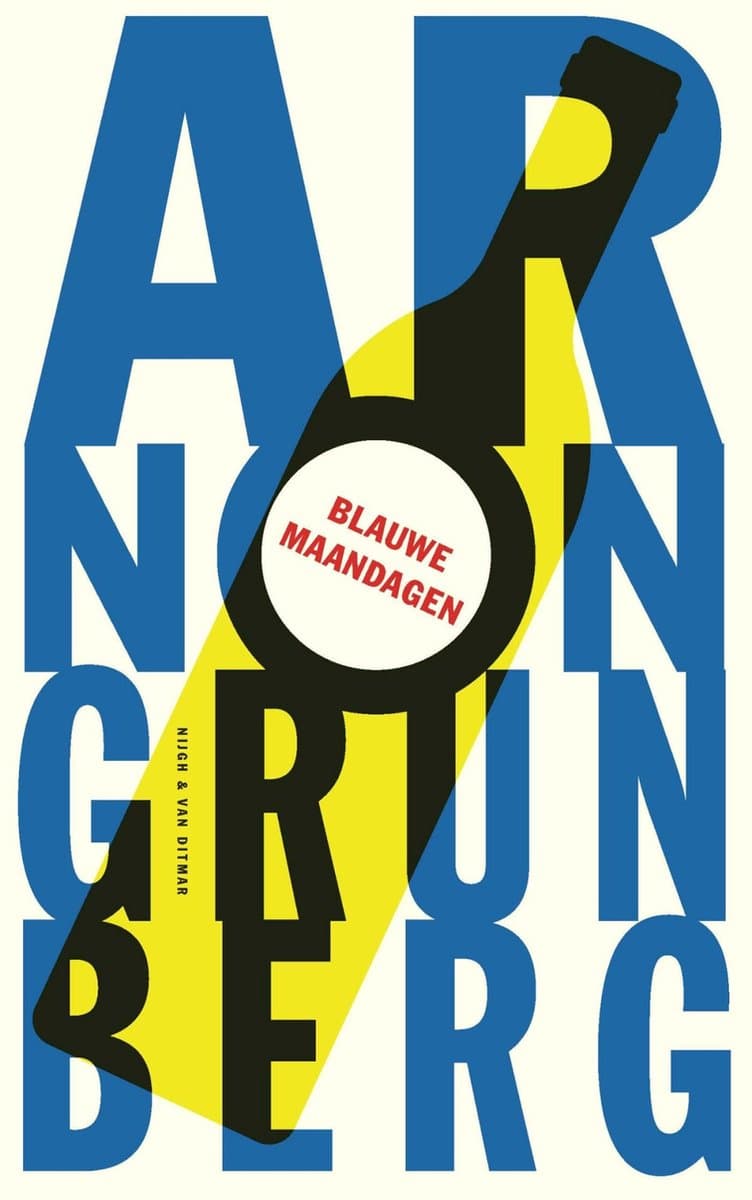

Blue Mondays

Absurd, unashamed and amusing’ well describes the life story of the character Arnon Grunberg, drawn up by the author of the same name. Little by little, the latter reveals what the former is like – a refined method that shows the writer to be considerably less harebrained than the Grunberg on paper, a small, Jewish, good-for-nothing guy with a grossly pale face, big nose, curly hair, glasses and pimples, who gives off an odor that begs for a pail of water and a big bar of soap.

Why isn’t he at school? What business does this jerk have here in the bars of expensive hotels and restaurants? Why is it so difficult to do anything besides lend your ear to this strange customer, once you’ve gone and sat down beside him? Actually this question has already been answered once you’ve admitted to having listened fascinated for a long time. Grunberg’s talent for tragicomedy – he likes Chaplin and Keaton, masters of slapstick – gets all the room it needs in these captivating confessions about his prematurely ended school career, about his sick father who insults the family care worker (and in the ensuing commotion relieves himself on the carpet), about his mother who used to be ‘the most beautiful’ and now empties a pan of spaghetti onto her husband (who motionlessly remains seated), about a girl Rosie (his first love) and the parade of prostitutes he later visits.

Grunberg carries the reader along through his life story – a series of stints for a jack-of-all-trades and a master of none – at a fast pace, passing by deeply tragic experiences and totally hilarious ones by turns, without pauzing too long by questions that can only allow for painful answers. Grunberg relates his story like a man on the run, perhaps running from the deadly quiet truth that life’s no more than a sham, a realization no aspirin can relieve. It’s therefore no surprise that Arnon wanted to be like an actor in the series Tender Is the Night since he was a kid, and that he would later try to be accepted to an acting school. At age twenty-two he puts on the suit of his father, who’s just died, and believes that in this disguise he can start a career as a gigolo. What else can you do except invent a tolerable existence, reforge it into a compelling story that intrigues, amuses, shocks and above all mustn’t lag, because then the curtain might go down after all. The book Grunberg has written in this way fervently opposes the threat that in the end, nothing can escape futility.

The debut of a born storyteller, who understands that humor is the est way of getting across the tragic side of a matter.

Trouw

A grotesque comedy, a rarity in Dutch literature.

NRC Handelsblad

In just four sentences he disposes of his grandfather’s pointless life. It’s hard to think how he might have set a better tone for what follows. (…) The penetrating tragicomicalpassages show what Grunberg is capable of: a lot.

De Volkskrant

.jpg&w=640&q=75)